In July 2021, Formula 1 ushered in a new era: a $100 million, five-year deal with Crypto.com, a platform for buying and selling cryptocurrency.

As if the deal wasn’t enough of a statement of intent, F1 Director of Commercial Partnerships Ben Pincus said in the sponsorship announcement that cryptocurrency was an “area we are very interested in.”

A year later, F1 had 16 crypto sponsors across its 10 teams.

Ahead of the 2024 season, the forecast for crypto’s role in the sport seems mixed: The 2023 season saw a dip in the sport’s crypto sponsors, with partnerships dropping to 13 across seven teams. But the crypto market had a good year, valued at $1.7 trillion at the end of 2023, compared to $871 billion a year prior, Reuters reported.

At this juncture, F1 could lean more heavily on crypto in the coming year — as indicated by Sauber’s selection of crypto casino Stake.com as their title sponsor — hoping the sector continues to grow despite its volatility. Or the declining trend in crypto partnerships, paired with advertising regulations and legal and financial troubles in the crypto sector, may signal a waning interest in the market.

Regardless of the path F1 goes down, it’s clear it is at a crossroads. And because of crypto’s association with abundant wealth, rafts of regulations and ethical concerns, it’s a true microcosm of F1 and the corporations that fund it.

Sponsorships in F1 are just as much of the sport as the racing, with over 300 companies represented across the 10 teams’ partnerships and suppliers and their logos proudly embossed on drivers’ cars and overalls. If F1 is the highest echelon of motorsport, it also has the most eyes on it and more advertising cash at stake with teams willing to pull some strings to keep brands happy.

The Athletic’s Luke Smith has compared the innovation needed to circumvent design regulations to the metamorphosis needed to similarly evade advertising and sponsorship regulations. This corporate chicanery has become a baked-in part of the sport, no better illustrated than through livery loopholes — the cracks teams and brands find to allow advertisements on the side of F1 cars, despite regulations that would otherwise prohibit them from doing so.

These loopholes have been around as long as sponsorships in the sport.

F1's corporate dawn

On track, the 1968 F1 season was revolutionary for its introduction of the front wing and full-face race helmet. Off track, 1968 would also mark the turning point in F1’s marketing landscape.

At the South African Grand Prix, Team Gunston ran the first F1 car with a painted sponsor livery. Driver John Love’s car, a privately entered Brabham, was covered in the cigarette company Gunston’s iconic burnt orange.

One race later, Lotus would run a red, gold and white livery on Graham Hill’s car to represent sponsor Imperial Tobacco Gold Leaf.

In the first quarter of the season, automotive giants Firestone, Shell and BP left F1’s sponsorship pool, pushing the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) to permit unrestricted sponsorships in the sport for the first time. Previously, cars reflected the colors of their teams’ countries of origin.

Over the next 56 years, as constructors increasingly relied on sponsors to fund teams, sponsorships became more diverse, as did team liveries and, subsequently, team brands and identities.

Sponsors would become synonymous with constructors: Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna’s era as McLaren teammates are easily recognizable by the red-and-white Marlboro McLaren. Michael Schumacher’s time in a Marlboro-red Ferrari over a decade later was equally emblematic.

McLaren’s Vodafone-era chrome livery of the mid-2000s would define Lewis Hamilton’s tenure with the team, and serve to complement boss Ron Dennis’ affinity for gray.

And you can thank water technology company BWT for Force India and Racing Point’s Pink Mercedes and Alpine’s Baskin-Robbins blue-and-pink livery of 2022 and ‘23.

Of course, sponsorship liveries have also been tied up with tales of infamy.

Haas’ 2019 Rich Energy black-and-gold livery would not only mark a year of poor performance (they finished P9 in the constructors’ standings), but also of controversy. The energy drink brand suddenly dropped Haas at the end of the season, citing aforementioned performance, but the company was also embroiled in its own drama, including the ousting of CEO William Storey amid accusations that Rich Energy copied the logo of bicycle company Whyte Bikes.

Over the past five decades, liveries have become synonymous with the identities of F1 teams. As crypto’s footprint in F1 grows, so too do concerns for the sector’s role in F1’s changing identity.

When does advertising become dangerous?

Everyone from finance experts to sports commentators have raised the red flag as beloved pastimes and cryptocurrency overlap. Not only does crypto advertising in sports pose ethical questions, but also credibility issues. It’s not so harmful for the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Shohei Ohtani to convince a fan her next sneakers should be New Balances. It’s another thing to take financial advice from an athlete or buy cryptocurrency because it's a team title sponsor.

Arthur Solomon, a former senior vice president and counselor at Burson-Marsteller and spokesman for the Seoul Olympic Organizing Committee, argued that regulators have a responsibility to ban cryptocurrency advertising in sports.

“There are professional investment advisors who are regulated by the government to give financial advice,” Solomon argued in an op-ed for CoinDesk. “The Federal Trade Commission and other government agencies shouldn’t permit someone, just because he can hit a home run or throw a touchdown pass, to give financial advice on public airwaves.”

Athletes, including Floyd Mayweather Jr., Shaquille O’Neal and Stephen Curry, have either found themselves at the receiving end of crypto lawsuits or accused of promoting cryptocurrency for their own gain, also known as “shilling” in the financial sector.

An odd collection of big-name celebrities were hit with legal charges by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in early 2023. From Lindsay Lohan and Soulja Boy to Jake Paul, the star-studded crypto circle used social media to promote TRX and BTT cryptocurrency, according to SEC legal filings. The commission argued that those involved failed to disclose receiving compensation for their posts. In a similar scandal, Kim Kardashian paid $1.26 million to settle a crypto dispute. The SEC said that, like other celebrities, Kardashian had failed to adequately inform followers of a $250,000 payment in exchange for promoting EMAX tokens on Instagram.

Celebrities and athletes trading or investing in crypto isn’t novel. However, the currency and trading platforms are often policed by gray policies that leave uneducated investors in legal trouble and fans financially vulnerable.

Even athletes starring in Super Bowl commercials aren’t necessarily protected depending on what they disclose. Concerns over 2022’s fan-dubbed “Crypto Bowl,” a reference to the glaring cryptocurrency branding and advertisements, changed the game. The 2023 Super Bowl looked a little different as Fox Sports insisted there would be no cryptocurrency advertisements.

Other sports are taking note.

As cryptocurrency stands on a shaky and volatile foundation, the same loyalty in sponsors F1 has cherished previously has seemed to subside. Between 2022 and 2023, crypto sponsorship turnover swelled. Ferrari dropped its blockchain backer Velas, Red Bull ended its Tezos contract and Williams Racing cut ties with Virtua.

Despite F1 teams rolling back crypto sponsorship and the U.S. cracking down on crypto crime, the highly volatile currency continues to grace more than half the grid.

From McLaren’s double crypto partnerships with OKX and Tezos to Williams’ sponsor Kraken to Alpine’s crypto exchange investor Binance, cryptocurrency seems like the new tobacco in F1.

Even as lawsuits ramp up, regulation remains vague and ever-changing; in countries with more strict laws that prohibit any kind of advertising or promotional material, motorsport teams are getting crafty.

Cryptocurrency’s ‘stake’ in racing

During the 2023 F1 season, Alfa Romeo routinely swapped out its Stake.com title sponsor logo for Kick, a streaming platform.

In host race countries with strict online gambling and cryptocurrency laws, a new paint job seems to do the trick for skirting regulations. Section 9.1.b of the FIA-issued F1 sporting regulations allows for constructors to change liveries mid-season if the FIA and the Commercial Rights Holder agree. A team’s two cars must be “presented in substantially the same livery at every competition” if the two bodies fail to approve the new livery.

Stake, a self-described “crypto casino and sports betting” online platform, shot up in gross gaming revenue in 2022 by nearly 25 times its $105 million 2020 revenue, reported the Financial Times (FT). In just eight years, Stake has transformed from an off-shoot of co-founders Ed Craven and Bijan Tehrani’s crypto-betting online dice game to a gambling platform with a retainer of high-profile celebrities and a revenue of $2.6 billion.

For a touring circus like F1, Stake’s operation in legally ambiguous areas plays to the team’s advantage. A sizable number of the six million accounts registered to Stake.com are located in Asian countries like Japan where cryptocurrency laws are fuzzy at best, FT found.

On Jan. 1, Stake F1 Team Kick Sauber, formerly known as Alfa Romeo, announced the team would be referred to as Stake F1 Team, with Stake.com acting as title sponsor. Stake is the first online gambling and crypto title sponsor to have its name in bold among the likes of Ferrari, Mercedes and McLaren.

The team will likely be referred to as Kick F1 Team in a handful of races in 2024, according to Autosport. In countries such as China, where crypto and sports betting advertising is banned, swapping Stake for Kick will likely be regulation.

But strangely, Kick’s principal stakeholder is Stake, with the company backed by Stake and co-founded by Tehrani and Craven. The temporary team name change serves as a convenient loophole for Stake shareholders, who will continue to profit from Kick.

It’s not uncommon for corporations to have subsidiary companies or to be principal stakeholders for other corporations. In fact, it’s a very convenient way to skirt regulations well within the confines of corporate law — almost as if corporate law was designed to benefit corporate conglomerates in the first place.

We’ve seen this in F1 before: After sweeping bans on tobacco advertising in the early 2000s, Ferrari swapped its Marlboro logo and Philip Morris International partnership with Mission Winnow, whose logo first appeared on Ferrari’s 2018 car at the Japanese Grand Prix. Mission Winnow is a “content lab” owned by Philip Morris International. Because Mission Winnow exists with so many degrees of separation from Philip Morris’ tobacco brands, it was able to appear on Ferrari’s cars (non-continuously) through 2021. Mission Winnow quietly renewed a smaller contract with Ferrari in 2022.

Stake’s switcheroo may be familiar, but the Stake-Sauber partnership marks a new era in motorsports, one that could see fans supporting teams with vague stakeholder names rather than the sport’s beloved auto manufacturers.

Online gambling and crypto involvement has surged in just a few years as the slippery slope of sponsorship slickens. In 2020, 188Bet Sportsbook scored an unprecedented deal as the official sports gambling and betting partner for F1 Asia.

In an odd shuffling around of illicit sponsors, crypto has become a scapegoat for teams with smokeless tobacco companies as title sponsors.

During the 2023 season, McLaren introduced three distinct liveries. On the surface, these Instagram-hyped reveals were nothing more than swapping out the McLaren’s papaya orange body to celebrate significant races on the calendar. However, along with fan-commissioned art came a new sponsor logo.

VELO, a self-described “modern take on nicotine,” stretched the length of the car at the Silverstone circuit. In the Netherlands, the company sponsored a custom fan-inspired logo spelling out “LOVE,” rather than its recognizable emblem. Ahead of the Singapore Grand Prix, McLaren teased its “stealth mode” campaign and pulled the cover off of a pitch-black paint job for the night race. The team’s nicotine pouch title sponsor was notably absent. In VELO’s place stood OKX, the second-largest cryptocurrency company.

In both the Netherlands and Singapore, tobacco product and electronic cigarette advertising is outlawed. Rather than outright declaring the motive behind switching out the bootleg backer, McLaren created a promotional strategy that built the new car design around fan participation, influencer social media campaigns and the potential for a gold mine of headlines.

F1’s return to the Shanghai International Circuit in 2024 poses issues for everyone involved. In a newly passed law, China banned online e-cigarette advertising and applied the country’s tobacco advertising laws to e-cigarettes and products, including deeming promotion in mass media, public areas, public transit and outdoor areas illegal.

Unlike in Singapore, McLaren won’t have the luxury of replacing VELO with a crypto stakeholder in Shanghai.

At the beginning of the crypto-craze, the People’s Bank of China was ahead of the curve in banning national financial institutions from dipping a toe in crypto. The regulation went into effect in 2013 and since has extended to prohibit most cryptocurrency activities and promotions, including Bitcoin mining.

While McLaren and Alfa Romeo may have swapped out a few logos, other teams are paying attention to McLaren’s debut sponsorship-swapping technology that graced the circuit at the start of the 2023 racing season.

McLaren teamed up with Seamless Digital to create a screen on each side of the cockpit that allows for a rotation of sponsorship names. AlphaTauri will adopt the technology in 2024.

As crypto takes over Big Tobacco’s hold on the sport, F1 operates more like a revolving door of sponsors rather than relying on one for a team identity. Even Stake’s title sponsorship contract is only for two short years. In 2023, F1 hit the 300 mark for the largest number of sponsors split among 10 teams in the sport’s history, according to Motorsport.com. Space on an F1 car, measuring roughly five by two meters, is limited. McLaren’s model for a commercial on wheels may be an increasingly popular option as teams swap out sponsors from race to race and year to year.

Crypto’s Moral Catch-22

But is crypto sponsorship such a bad thing?

It’s difficult to pinpoint why exactly cryptocurrency sponsorship feels so icky.

The Seven Pillars Institute argues that many of the digital currency’s ethical concerns stem from a lack of a central regulatory authority. In the U.S., crypto lawsuits are handled by the SEC, but its loose definition as both a trading commodity and currency leads some scholars to argue it should fall under the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

The SEC has only recently made a dent in the mountain of sketchy crypto cliques.

In the groundbreaking Centra Tech case, a duo of Atlantic Beach twenty-somethings jumped on the crypto craze after losing their money with a botched Miami-based exotic car brand. Raymond Trapani and Sam Sharma founded an initial coin offering (ICO), alongside Robert Farkas and set up a fraudulent cryptocurrency business that aimed to revolutionize crypto by creating debit cards, allowing investors to spend their crypto in real-time. However, everything from the company’s team LinkedIn profiles and college degrees to the Visa and Bancorp-backing was fake.

The business wasn’t only built on false pretenses, but the concept itself never saw fruition. The cards that Centra Tech had celebrities like Mayweather Jr. and DJ Khaled promoting were nothing more than prepaid Bancorp cards manually loaded with cash.

As celebrities and athletes bought the Centra Card hype, everyday investors who were influenced to buy into the platform suffered significant financial losses as the company unraveled.

Centra Tech’s SEC case wrote the “how to take down crypto” rulebook for the FBI. The Department of Justice used the case to send a message to the crypto market in a time of rampant fraud. One member of the company faced eight years in federal prison while the founder behind the operation left the courtroom with no prison time despite pleading guilty to a host of charges, including securities fraud, according to court documents. The SEC defines “securities” broadly as a range of investment interests issued to startup funders.

The whole scam had a familiar flavor reminiscent of a Catch Me If You Can series of scheming with a Henry Hill mobster main character.

Cryptocurrency began as a way to reinvent the financial sector so customers didn’t have to trust big banks with their money — a kind of anarchism. The opposite occurred. While some ICOs began as legitimate ways to digitize a global currency, the unregulated market without a central financial authority became a cesspool for scams, like Centra Tech, that fostered even more mistrust. The ICO title also allowed crypto business owners like Raymond to print money, putting the power of financial institutions in the hands of anyone who could create a website and had a chunk of change. As an epidemic of scamming and illegal arms and drugs trading tainted crypto’s original concept, the biggest news outlets were calling the beginning of the crypto craze the best time to be a money launderer.

Based on its original concept, an estimated $4.9 billion was invested in cryptocurrency startups and ICOs in 2017. Roughly 80 percent of those companies were scams, according to the Satis Group. In 2019, the Wall Street Journal reported that $4 billion was tied up in cryptocurrency scams, many of them Ponzi schemes.

Even the largest cryptocurrency platforms with legal roots, like in the case of FTX, have been fraught with fraud and SEC violations.

Early on, the co-founders of Stake sought advice from Dan Friedberg, who went on to become the chief compliance and regulatory officer for FTX, a cryptocurrency exchange platform that collapsed in late 2022. FT reported that Friedberg previously gave advice to Ultimate Bet, a cryptocurrency gambling site that was fined for software espionage used to bet against players.

Mercedes-AMG Petronas partnered with FTX until the company crumbled in November 2022.

FTX rose to become the third-largest crypto platform with a value of $32 billion. As news of the company’s close relationship with Alameda Research trading firm became public, customers withdrew investment. Within a couple of days, the platform filed for bankruptcy. A year later, Sam Bankman-Fried, FTX’s founder, was found guilty of seven conspiracy and fraud charges, including two counts of wire fraud conspiracy and two counts of wire fraud. Bankman-Fried denied the charges. In November, FTX sued Red Bull crypto sponsor Bybit for $953 million in assets and cash, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Tezos, one of McLaren’s current cryptocurrency sponsors and former Red Bull partner, was the biggest ICO when it launched in 2017. Despite its success, the company faced a handful of class action lawsuits, one alleging securities fraud that Tezos settled for $25 million, and a fine from the U.S. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) for failing to reveal the founder set up a crypto company while still working at Morgan Stanley, according to Reuters. The SEC has also recently targeted Alpine sponsor Binance and Haas sponsor OpenSea. The regulatory body sued Binance for an alleged sale of unregistered securities while a former OpenSea product manager was sentenced for NFT insider trading for personal financial gain.

The real ethical question, at least in sports, lies in whether consumers believe teams have their best interest at heart when promoting crypto platforms. Companies may recover and celebrities can shell out millions, but, at the end of the day, investor and fan dollars are at stake.

That sinking feeling about the ethicality of crypto and its involvement in F1 is a longstanding sports tradition. F1 has long relied on the tobacco industry for money and publicity. Though big tobacco has had a five-decade love affair with F1— compared to crypto’s short situationship — the two industries’ involvement with F1 shares stark commonalities.

F1’s tobacco ties ignite controversy

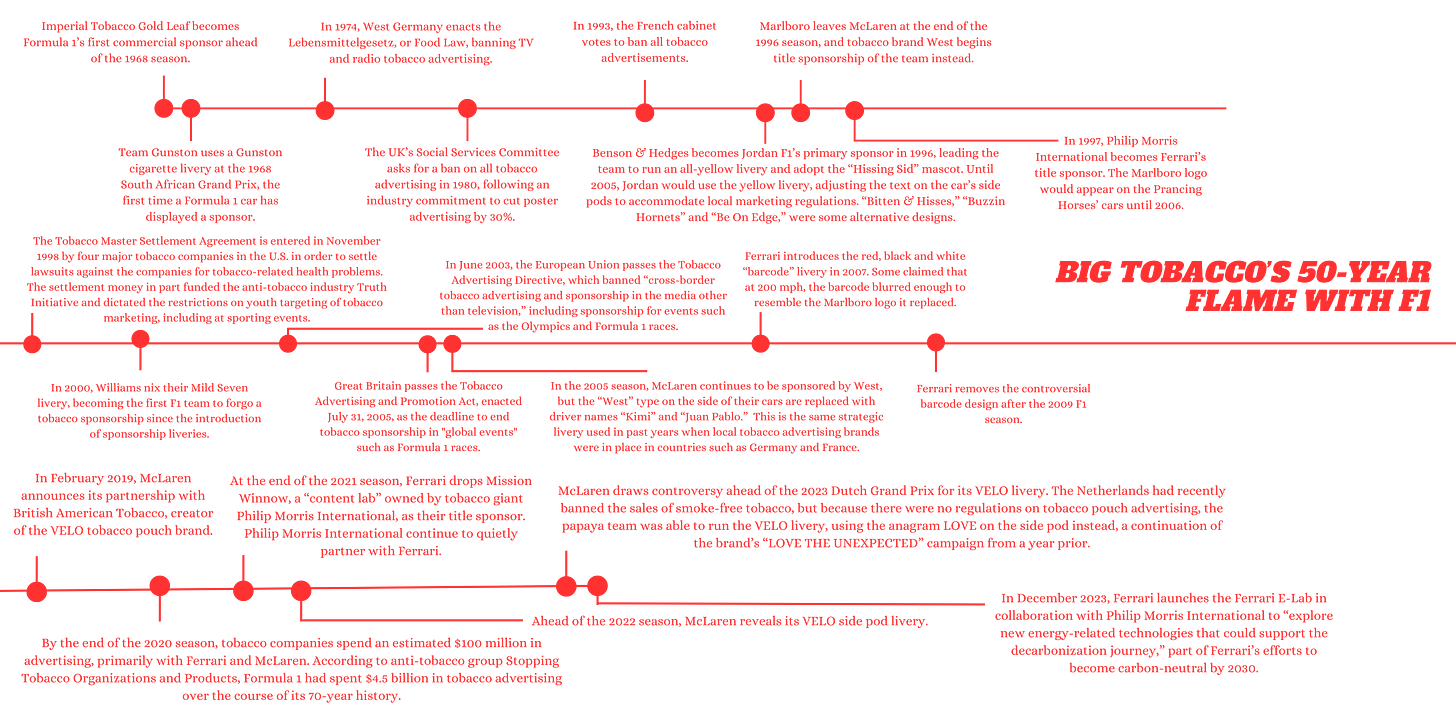

The tobacco industry’s involvement in F1 since the inception of sponsorship liveries highlights how partnerships with the sport serve highly regulated corporations.

As countries across Europe began to regulate tobacco advertising, Big Tobacco got smart, changing how they engaged with the public — who was growing more skeptical of the industry — and finding clever ways to navigate advertising bans.

Jordan F1 team, sponsored by Benson & Hedges, was easily recognizable sporting a bright yellow car with black text proudly displaying the cigarette brand. But as tobacco sponsorship bans swept through Europe in the 1990s, starting in Germany and France, Jordan got creative. The 1997 car replaced the “Benson & Hedges” text with “Bitten & Hisses,” an homage to their de facto snake mascot Hissing Sid. The team was likewise the “Buzzin Hornets” from 1998 to 2000. In 2002, the team adopted the slogan “BE ON EDGE,” before Benson & Hedges and Jordan parted ways in 2005, after the enactment of Great Britain’s Tobacco Advertising and Promotion Act.

Teams such as McLaren, sponsored by West in the late 1990s and early 2000s, took similar evasive action with their liveries, replacing the “West” side pod text with their drivers’ names, using the same font and coloring.

Despite tobacco’s growing unpopularity in the early 2000s, cigarette companies were able to continue to grab ad space because of how complementary their product was with other F1 sponsors, such as TicTac (which implicitly promised to rid a smoker’s bad breath) and Budweiser beer (which helped reinforce a smoker’s image as rugged and masculine).

In times when tobacco commercials were banned across Europe and the U.S., the Marlboro logo on a car’s side pod could regularly be seen on TV. Moreover, if a brand’s logo was slapped on a prominent part of an F1 car, and a photo of that car was used in another, unrelated ad, that brand would have increased exposure from a third party — having a spot on a livery was a true bang for cigarette companies’ buck.

Crypto companies have taken advantage of similar loopholes. At the 2022 Singapore Grand Prix, crypto advertisements were banned as part of Singapore’s larger ban on crypto advertising. But despite efforts to curtail on-track evidence of crypto’s support of F1, logos on liveries and race suits made the ban futile. As Sergio Perez lifted the trophy on the podium, the Bybit and Tezos logos were clearly visible on his racing overalls.

Netflix’s “Drive to Survive” has also created a third-party effect for F1’s recent sponsors. Though former Mercedes crypto sponsor FTX collapsed in November 2022, its logo would continue to appear in perpetuity on season 5 of “Drive to Survive,” giving the disgraced company — as well as other former sponsors — free air time.

The sunsetting of tobacco’s support for F1 could predict crypto’s similar fizzle.

Cigarette smoking in the U.S. peaked around 1964 before the United States Surgeon General’s Reports illustrated the health risks associated with smoking. Three years later, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) noted that it was “impossible for Americans of almost any age to avoid cigarette advertising.”

After Reader’s Digest’s publication of the report in plain terms, more people learned about the adverse effects of smoking. A 2014 review in Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers found that in 1965, 42% of U.S. adults were smokers, compared to less than 20% by 2011.

Public opinion of cryptocurrency since Bitcoin’s 2009 introduction has similarly faltered. Though 39% of adults who are familiar with cryptocurrency reported being not at all confident in its reliability and safety, that number grew to 75% in adults unfamiliar with cryptocurrency, the Pew Research Center found in a March 2023 survey.

While similar in the trajectory of public opinion and the ability to evade sponsorship regulations, Big Tobacco has been regulated and researched and has simply existed longer than cryptocurrencies. Since 2005, the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) has worked to address illicit tobacco trade, investment, advertising, promotion and sponsorships. The FCTC includes over 180 parties, including countries in the E.U. and was the first global public health treaty.

Big Tobacco’s opponents may have argued this effort has not done enough to stymie industry growth, but there has still been abundant research on the short- and long-term effects of smoking spanning almost a century. Industry marketing strategies have been similarly researched and understood.

Despite heavy regulations, Big Tobacco’s power endures. The FTC reported an increase in cigarette sales in the U.S. from 202.9 billion in 2019 to 203.7 billion in 2020, the first increase the commission has measured in 20 years.

The sheer survival of the industry is part of what makes it unique. It’s been entwined with F1 for over 50 years, creating some of the sport’s most iconic liveries, with regulatory loopholes allowing these liveries to become synonymous with teams such as Jordan, McLaren and Ferrari. That type of longevity no longer really exists in the sport today, as demonstrated by the increased use of Seamless Digital’s rotating screens for sponsorship ads.

It’s likely that F1 teams won’t have trouble continuing to find sponsorship funding in one way or another, but the quickly shifting tides of cryptocurrency and brand longevity have threatened a key piece of F1’s identity: its branding. F1’s dwindling reliability on long-term sponsors is congruent with younger generations’ attitudes towards brands. A McKinsey & Company survey of Gen Zers in the U.S. and U.K. found that 62 percent of Zoomers were open to purchasing an item outside of their favorite brand, and 50 percent would be open to switching brands if an alternative were cheaper or of better quality.

In some ways, F1’s rotating door of sponsors is a good thing: It means companies are being regulated and held accountable. But the sheer number of sponsors, many of them short-lived, could also be a harbinger for a new era of F1 where the iconic liveries that defined the careers of so many teams and drivers no longer exist.